Understanding Your Stock Options (ISOs and NSOs)

Stock options are one more way your company can grant equity as part of your compensation package. This type of grant is different from an RSU grant in that you don’t receive something that automatically turns into stock. Instead, with options, you receive an “option” to buy company stock at a certain price during a certain period.

In this post, we’ll give you the details you’ll need to know to understand how this type of equity can affect your financial plan. For an overview of all equity compensation, refer back to our post Where to Start When You Have Stock Compensation.

Many of the clients we work with who have options work at smaller, non-publicly traded companies. These types of companies give options as part of their initial job offer in lieu of higher salary, and/or as a retention tool for high-performing employees. We’ve also worked with clients at large public companies such as Facebook, Google, and Peloton that offer stock options.

Terminology

If you’ve been granted options, you’ll want to understand a few key details that are provided in the documents you’ll receive, or terms that you may hear others discussing.

Grant Letter, Grant Notice, or Award Letter – This is the document that describes what you are receiving. It will include the number of options, the strike price, the grant date, the vesting schedule, and the exercise period. This information is specific to you and your award.

Stock Option agreement – This is the document that gives more details about the plan in general, such as what the award means, the tax ramifications, and other provisions like the transferability of options.

Vesting requirements – Options usually vest over time. Cliff vesting is when a large chunk of the options vest at the same time. In other cases, options vest monthly or quarterly. It’s also possible there are additional requirements (like performance metrics) besides the passage of time for options to vest. These will be spelled out in the documents you receive upon grant. Not every grant from your employer may have the same vesting schedule, so pay attention to each one.

Strike Price – The price at which you can purchase stock during the exercise period. Also known as the exercise price.

Fair Market Value – The current market value of the stock. This can be determined by the price of the stock on a listed exchange if the company is public. For private companies, there is typically a value published by the company, or it could be a value established by a 409A valuation, an assessment by a third-party, independent appraiser.

Bargain Element – The amount of the discount you receive by being able to purchase the shares at the lower strike price. The bargain element is the difference between the fair market value and the strike price.

Under Water/In the Money – These two terms refer to the relationship between the strike price and fair market value. If the fair market value is lower than the strike price, the options are “Under Water” or “Out of the Money” – they really don’t have any value. Why would you purchase something for more than you can sell it for? If the fair market value is higher than the strike price, the options are “In the Money” and they have value.

Exercise Window/Expiration Date – After the options vest, this is the period of time during which you can decide to purchase the stock. It’s usually several years – and can be as much as 10 years. This is a lot of time during which the stock price can fluctuate and your option to purchase it can be worth more or less.

Administrator – Once your options are granted, there is an outside company that keeps track of when they vest and facilitates exercising the options and holding the resulting shares. You’ll receive login information when you receive an option grant and you’ll need to log in and “accept” the grant. Popular administrators are Fidelity, ComputerShare, and Morgan Stanley.

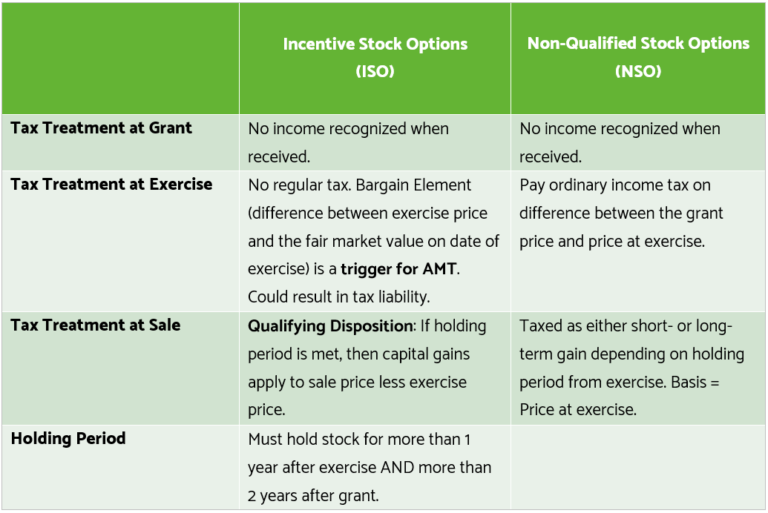

Tax Implications

Stock options have different rules depending on whether they are ISOs or NSOs. One thing is the same though, in almost all circumstances, there’s no tax impact when the options are granted or when the options vest (i.e., become able to be exercised). This is in contrast with RSUs, which cause you to have taxable income when they vest. In order for options to have a tax impact, you have to actually do something. Let’s start with NSOs because they are less complicated (but also less beneficial).

NSOs

When you exercise NSOs, the important things you need to know are the exercise or “strike” price, and the market value of the stock. You will be responsible for paying taxes on the bargain element when you exercise. This income is taxed just like your regular income. The market value at exercise becomes your basis in the stock and your holding period starts when you exercise.

In the future if you decide to sell the stock, the amount of gain (or loss) is calculated from that basis. The determination of short-term or long-term capital gain tax rates comes from how long you hold the stock. Long-term capital gain rates are usually lower than short-term rates, but waiting to sell can come with risk of the stock declining and wiping out the tax savings with investment losses.

What happens once you sell the shares you’ve purchased? As time goes on and the price of the stock fluctuates, your stock will either be worth more, or worth less, than the original basis. If you sell it when it’s worth more, you now have a capital gain that you must pay taxes on. If you sell it when it’s worth less, you have a capital loss that you may be able to deduct on your tax return.

It’s important to understand the difference between the “income” tax you pay upon exercising, and the “capital gain” tax you pay upon selling. They are two different things.

ISOs

So what about ISOs? Those are a little more complicated. Unlike NSOs, the bargain element is not automatically taxable income at exercise. In a second, we will discuss how it could be taxable income, but let’s assume it isn’t. If you exercise and hold the stock for more than 1 year after exercise AND more than 2 years after grant, the tax on the bargain element could be taxed the lower capital gains tax rate, rather than your regular income tax rate. This special rule can save you a lot of money in taxes.

There is a caveat to this rule and it involves Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). Many people don’t know that there’s a second set of tax rules always running in the background to the normal tax rules. The Alternative Minimum Tax is a set of rules created in 1969 to make sure wealthy taxpayers paid some tax instead of being able to use the regular rules to avoid taxes. Since the tax reform of 2018, AMT applies to fewer taxpayers than before so many people forget it exists.

The bargain element on ISOs is one place people get tripped up by the AMT. It is one of the few adjustment items that can trigger the AMT to apply. If this is the case for you, it’s important to work with an experienced accountant who can help you navigate it. Depending on the rest of your tax situation, AMT may be more or less likely to apply to you if you exercise ISOs. One strategy that is used frequently is to exercise just enough ISOs to stay below the AMT threshold.

Planning for Options

As I mentioned above, the tax implications are one way we help clients plan for stock options. Beyond taxes, there are more decisions to make when it comes to options. And unlike RSUs, you must do SOMETHING to make them valuable to you at all. And also unlike RSUs, it could be the case that your options end up being worth nothing – either because they are under water, or your company never becomes publicly traded and the stock is never worth anything. One other important difference between options and RSUs is that you need to pay something to exercise them.

For many workers in the early tech boom, options were the cool thing to have and could change their financial picture overnight. They can be a little like buying and holding a lottery ticket. Again, it’s important to assess the value of this investment in the context of the rest of your financial situation. If you must exercise with cash, you’ll want to ask yourself what happens if the stock ends up being worthless and your investment goes to zero.

As if the decisions that need to be made for options weren’t enough, there can also be the ability to “early exercise” stock options if you work at a private company. You can also do something called a “section 83b election” to pay taxes early on unvested options in the hope of saving money down the road. If you’re thinking that it seems risky to purchase stock in a company without being sure it will have value, and then on top of that to pay taxes on something that’s value is uncertain, you’re right. These advanced strategies are not for everyone.

Since options require more than one timing decision (when to exercise, when to sell), we’ve seen some truly unfortunate outcomes. Some people don’t do anything, and their options expire without ever having been exercised. Others are out there exercising every option they ever have, even if it’s not a good financial planning decision.

As for timing on selling stock, inaction rules the day as well. We’ve seen clients who come to us with years of stock accumulated from their option exercises. There are two challenges with this situation. Clients get emotionally attached to watching the value of the stock grow and can’t let it go. Or, the stock price has dropped since they exercised and they don’t want to take a loss.

As with holding stock granted as RSUs, the other challenge with stock purchased through options is the economic and investment risk taken by working and investing in the same company. There could be situations where your job could be in jeopardy at the same time the company stock is sliding. You may lose employment right as your investment is becoming less valuable. On the other hand, if you are advancing in your company rapidly, you may be getting more and more options. If the price continues to rise, it can be painful to sell shares and pay taxes on those gains.

In these types of situations, it’s helpful to have a financial planner who understands your full situation. For example, with clients who are emotionally attached to their company stock, we help them set up a plan for diversifying their investments. This could mean selling all newly exercised shares but keeping the old ones. It could also mean selling old shares over time regardless of what the stock price is doing. Finally, it could mean divesting of the stock completely to fund another important goal like buying a house.

We love helping clients understand their stock compensation plans. If you have questions about your stock options, please reach out and set up a complimentary introductions call!